I have a confession to make about recent comics. I don’t read them nearly as much as I used to. I tend to get attached to a title, buy a trade, but I’m not showing up on restocking day the way I did. I recently finished all four volumes of I Hate Fairyland by Skottie Young published under Image Comics; before that I finished all the volumes of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Last Ronin by Kevin Eastman, Peter Laird, and Tom Waltz written under IDW Publishing. The last time I got hooked into a major title under the big two was Heroes in Crisis by Tom King back in 2018-2019. I think it appealed to the psychologist in me. I had a lot of ups and downs with that title (as did we all, it seems).

I’ve honestly hit a wall with comics because there are so many options, the market is saturated and it can be hard to find the weird independent gems without going completely local. Like my father before me unfortunately, seeing certain properties turned on their head by writers who don’t seem to understand them has me….acting like a sixty-something year old man.

The thing is, I’d like to as obnoxious about comic books as I once was. I want to be in the comic shops. I’ve finally moved past my post-quarantine mindset even as I hesitate and find it inadvisable to be outside like nothing is wrong.

Comics tend to have life cycles as different writers and artists gain and lose the capital, the endorsement of the throne. Ultimately, each character is the property of their editors and the editors decide the course of their life. You have an editor that wants everything turned around, has a vision that doesn’t jive with you, the reader, and you end up with comics burn out.

So something that has….set me off my dinner.

I am a character driven sort of lad. I have a lot of opinions about the course of stories following the actions that make the most sense given a character’s backstory, the cultural atmosphere represented, how that character’s behavior is formed. I also care a lot about character creators, how their own stories and politics and styles fold in.

It is lazy criticism to say that something is out of character. I’ll make the argument, and I’ll also say it’s lazy. It’s privileged nonsense. Those characters are malleable to their writers and their writers are trying something. If it works you call it brilliant, if it doesn’t work you sit and say ‘bah, why fuck this up?’

And it’s therefore not bad writing, it just doesn’t work for me.

I love JLI. I love JLI very, very much. Do I think they threw away some possibly amazing Guy Gardner stories in order to make him more fun, sure. Do I think they hinted at what Guy Gardner was capable of—better than anyone else. A qualm like this isn’t a make-it-or-break-it scenario. You can let characters have fun and still have dynamic, troubled stories, and come out on top. I think sometimes we—the proverbial we—forget that comics are fun.

You wanna fight me on Booster Gold? Fuck. Please. Do.

Enough apologizing.

And enough DC.

Here’s something that truly doesn’t work for me. And it’s something that could have been brilliant.

A brief history on J Jonah Jameson.

There’s a lot, there’s a lot that’s been tweaked and changed over time and no summary, no character’s backstory is ever going to be complete. This is the J Jonah I know. And it’s defined by the line, “No one’s a hero every day of the week.”

This was an invention of the 2003 Behind The Mustache, a story in Spider-Man’s Tangled Web issue 20. I think this is one of the nicer attempts at explaining the ups and downs of J Jonah’s pursuit of Spider-man character assassination since his introduction in March 1963 along with the rest of the Spider-Man title.

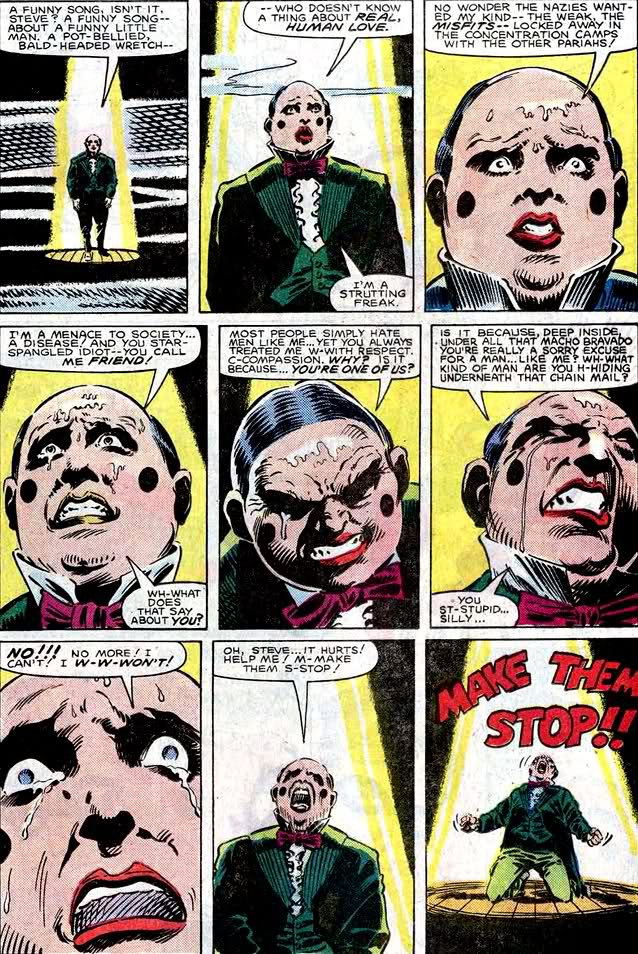

I think one of the things which we release too quickly from our reader’s perspective, we suspend the disbelief too completely, is that objectively J Jonah is right. It’s only through dramatic irony that we see him as buffoonish. J Jonah is a person suspicious of costumed vigilantes, with a wealth and breadth of life experience dealing with bad guys and high stakes. I think by inserting the line “No one’s a hero every day of the week” we give him a sympathetic reason for his hard-line stance against people with no accountability.

It used to be that being a war correspondent had been enough, but the times and readership changed. The further we move away from Vietnam and Korea and World War II, the harder it was to understand a character deeply suspicious of a ‘nice guy’ with unchecked power.

A huge problem which Marvel writers often address is the issue of accountability and I think it’s one of the chief selling points of Marvel vs. DC plotlines. The Civil War storyline in 2006-2007 addressed it head on—and caused a lot of friction among the fans. It essentially took a polarized society and reflected a mirror back on itself of how these tensions play out within the Marvel microcosm. Now, of course, not everyone was on board with Marvel society in chaos and it was all retconned and conscripted into turning out fine (it uh….was not to improve neatly for actual society).

The Behind the Mustache story is essentially this: J Jonah’s biological father is MIA, his foster father/uncle David Jameson is a decorated war hero—and deeply abusive of his wife and son. “No one’s a hero every day of the week,” and “Even the real heroes can’t keep it up all of the time,” are J Jonah’s core beliefs–ones which a younger generation could connect with more easily than wartime perspectives.

This story, adding to the mythos in this way, was brilliant. It was brilliant for a reason Stan Lee always held dear–Spider-Man, in particular, is a kid. He was written and designed to appeal to youth. Not just as a sidekick, but as the star, someone on a constant journey up.

J Jonah, in contrast, isn’t that kid anymore.

J Jonah has several issues in Spider-Man titles in which he is handed the baton and Spider-Man is barely present; namely, Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man # 80 (1983), Web of Spider-Man #52 (1989), and Spider-Man’s Tangled Web #20 (2003). J Jonah is considered, or was considered such an important character that writers consulted Stan Lee and asked him to come out of retirement to script the marriage of J Jonah Jameson to Marla Madison.

It’s because of something Marvel does that other publishing houses do on a smaller, less visible scale.

For instance, I was really pleased with the Loki show that Marvel Studios produced for making Owen Wilson have a mustache. Without the mustache, he couldn’t have been Mobius M. Mobius, because without the mustache it wouldn’t be Mark Gruenwald. September 1987, Mark Gruenwald became Marvel’s Executive Editor. It only made sense when the Time Variance Agency was created—first in a four shot series in Fantastic Four—that all of the TVA agents be clones of Gru. He was in charge of continuity for the whole Marvel Universe, inside and out.

Writers particularly in the 80s were very protective of J Jonah storylines, a tradition that waxes and wanes.

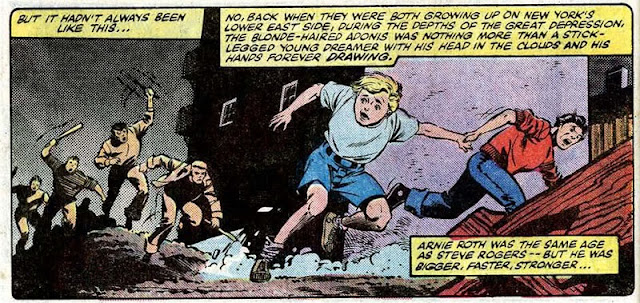

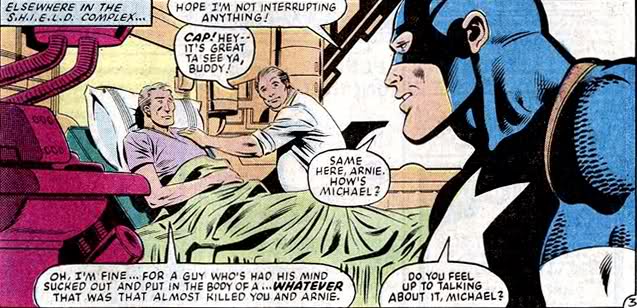

J Jonah was bullied as a child and beat up his bullies. He married Joan, father of John Jonah III. He was a correspondent to the Howling Commandos, a correspondent in Korea. He became a widower, used grief to focus on publication, and eventually became the owner of the Daily Bugle—making good on his boastful, loud decrees that someday it would be his name on everything.

He was greedy, belligerent, stubborn, demanding of his employees, but with a reputation for integrity. I think Sam Raimi struck on it nicely, it’s one of my favorite parts of Spider-Man (2002). Even being strangled by the Green Goblin, which, I’d listen to Willem Dafoe– JK Simmon’s J Jonah says he doesn’t know where the pictures of Spider-Man come from.

J Jonah is a long time crusader for civil rights, campaigns for labor and mutant rights, is repeatedly shown to be disgusted by racism. There are multiple times in which J Jonah protects Spider-man, no matter the personal cost.

Without fleshing out every character development and gut punch of more than fifty-nine years of comics, the long and the short of it is this:

J Jonah doesn’t feel protected to me the way that he was. In people’s need to reinvent and do something fresh with the character he’s gotten increasingly away from who he is.

J Jonah Jameson is Stan Lee. Stan Lee said, “Grumpier” though his artists might have had vague shrugs about that.

Spider-Man writers Jerry Conway and Tom DeFalco agreed that J Jonah was the closest Stan Lee came to a self-insert character, a surprisingly honest one, with Conway stating “Stan is a very complex and interesting guy who both has a tremendously charismatic part of himself and is an honestly decent guy who cares about people, he also has this incredible ability to go immediately to shallow. Just, BOOM, right to shallow. And that’s Jameson.” He went on to say that he read and wrote J Jonah in Stan Lee’s voice, at least one time directly quoting a speech Stan Lee gave the art department into a Spider-man comic.

It puts a different spin to imagine the boastful, demanding, ‘get me pictures of spider-man’ when you know it was literal.

Spider-man was one of Stan Lee’s favorite properties. He was quoted in 2018 as saying that Spider-Man was the most like him because “nothing ever turns out 100 OK”, though two years later in 2010 when asked about J Jonah he would say “You caught me… I thought, if I were a grumpy, irritable man, which I am sometimes, how would I act? And that was it. So, you got me.”

Spider-man was aspirational. It was something Stan Lee referenced back to constantly. It was something he talked about in interviews as changing the course of comic writing. But mostly, Stan Lee liked Spider-man. Spider-man was someone relatable, someone he cared about.

After 2002 I remember him giving an anecdote in an interview. For the 1989 Batman movie premiere, Bob Kane had picked him up in a limousine and outside the theater, Bob Kane had told him something to the effect of, ‘You don’t see Spider-Man up there, do you?’

Stan Lee was grinning, so happy to tell you that Bob Kane was an asshole to him, and that Batman (1989) had made 411.6 million.

Spider-Man (2002) had made 825 million.

You must be logged in to post a comment.